Christmas Eve Traditions in Liguria

Myths, Traditions, and Superstitions of Christmas Eve in Liguria, the Most Magical Night of the Year

The night of December 24, Christmas Eve, is one of the most magical nights of the year, along with New Year’s Eve, Epiphany, the eve of May Day, and the one preceding the day of St. John the Baptist (June 24). If you want to know the Christmas feast menu in Liguria, click here. Below are some curiosities about this particular time of the year. This text is taken from “Il cerchio del tempo. Le tradizioni popolari dei liguri” by Paolo Giardelli, Sagep 1992.

On Christmas Eve, the spheres of the sacred and everyday life seem to draw near, and everything is experienced with a sense of anticipation and hope; everything takes on a special meaning. It has always been believed that time, at this moment of the year, suspends, lightens, in anticipation of the divine irruption into the world. In reality, this is part of the Celtic conception of time that has come down to us: the night is the gestation of what will happen during the day—life.

A Special Moment for Children and Animals

Children, representing the future, are honoured with gifts: in eastern Liguria, they would excitedly place a plate on the windowsill; a white spirit with golden wings would descend to deposit sweets, nuts, and plums. Animals, for example, would be able to sense this atmosphere, perceiving supernatural spirits in the air; their behaviours were referred to as signs of the arrival of the revealing future. Animals received special attention: stables were cleaned with the broom typically used at home, which was then designated for that purpose and replaced at home with a new one. The animals’ bedding was changed with new chestnut leaves, and in Val di Vara and Val Fontanabuona, it was customary to let the animals taste the dishes of the Christmas Eve dinner.

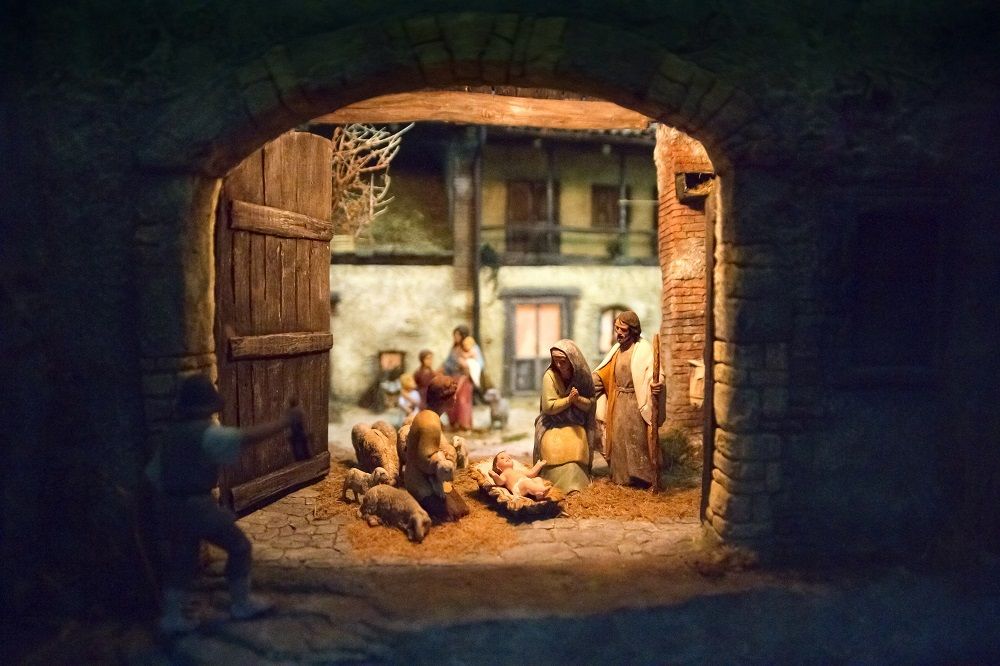

The Arrival of the Baby Jesus

Jesus, as we know, was born between an ox and a donkey, but this is not found in the Gospel. It actually stems from an error in translation from Greek (literally, the Baby Jesus is said to be born “between the two ages,” but in ancient Greek, the characters for “ages” and “animals” resemble each other, leading many astray). However, this has led to popular beliefs such as the one that sees, at the stroke of midnight, Baby Jesus visiting the stables first: it was believed that his arrival would momentarily give the animals the ability to speak, and they, kneeling before him, would recount all the sufferings and injustices suffered by humans throughout the year. However, it was impossible to participate in that conversation: one would be harshly punished.

The Magic of the Night of December 24th

Everything, on the night of the 24th, becomes imbued with strength and sacredness, including the Christmas lunch: in Val di Vara, bread and broth were kept to cure diseases in the eyes of the livestock. With bread, they also treated children’s sore throats, being careful to place it on the table on Christmas Day, cut it into a cross shape, and not eat a single crumb until the end of the festivities. Nothing was thrown away on Christmas Eve: the fireplace’s charcoal was believed to be effective against landslides after many days of rain; the flour used for kneading, the oil from church lamps could not be wasted but were reused. The night of the vigil would also have effects on the seeds, generating domestic and excellent fruit.

Water holds great importance: the source of life before, at this particular moment, it would have exceptional virtues: a girl who, at the stroke of midnight, drew water from a fountain or well would be extremely fortunate because she would marry a wealthy man and be happy. The crowding of unmarried girls at the fountains thus created quite a few quarrels.

However, if, during Christmas night, the forces of good are powerful, equally so would be the forces of evil: traditionally, werewolves are born that night, and only on December 24th could healers and sorcerers reveal their secrets to cure the evil eye, under the penalty of losing their powers.

In Val di Vara, protection against the evil eye involved putting spun hemp thread at the stroke of midnight in the stables, to ensnare anyone who wanted to cast the evil eye on the animals.

The Importance of stars

On the day of the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year (this year on December 22), like that of St. John the Baptist, it was very propitious for gathering herbs. Hellebore, “Dragon Herb,” effective against some livestock diseases, was collected in Zignago and Valfontanabuona. In church, the faithful brought heather during the journey to church, later hung in the stable to protect the livestock.

On Christmas night, like all the nights in the twelve-day cycle (from the night of December 24th to January 6th) and like that of All Saints, the dead would also return to visit the places of their lives: hence, a set table was left for them, or a poor person was invited to dinner, believing that they hosted the soul of the deceased. Hearing the bells ring, leaving a candle and a log burning in the fireplace represented a gesture of safety and tranquility.

A Large Log in the Fireplace

According to an ancient tradition, a large log was placed in the hearth, which would continue to burn from the evening of Christmas Eve until Epiphany and New Year’s. The fire had purifying and auspicious action. In Liguria, the preferred log for its long duration in the fireplace is olive, enriched with juniper branches, considered auspicious. The first bite and the first sip of wine were thrown into the fire, similar to what was done for the commemoration of the deceased. It was believed that the log protected against thunderstorms: in Val di Vara, charcoal was collected from the hearth on Christmas Day to put it back a little on the fire every evening until the new year. Charcoal was also effective against some animal diseases. Some old individuals could even derive auspices from the burning log or from wheat grains thrown into the extinguished hearth with a procedure called “u ziguà“: if the grain rose uphill, the harvest would be abundant, scarce otherwise. U ziguà continued with cereals and even with chestnuts, month by month.

The Christmas Eve Bonfire

The village bonfire, lit on Christmas Eve, was a gathering place for socializing. In Valle Argentina, Nervia, Bevera, and Roja, large bonfires and fires are lit on Christmas Eve, which are believed to burn to warm Baby Jesus. In the past, “u foegu du Bambin,” as it was called, burned until Epiphany. Even today in Vallebona, Airole, Castelvittorio, the task of finding wood is entrusted to boys who “stole” wood from the stacks with the phrase “Pe’ u foegu du Bambin!“. Also in Triora, Carpasio, and Andagna, a large bonfire was usually lit in the church square, while in Badalucco, after the Midnight Mass, nougat prepared with two large tongs was offered on the bonfire.

In mountain villages more connected to pastoral traditions (Mendatica, Briga, Pigna, and others), a lamb was brought during the Midnight Mass; in the arms of the oldest shepherd and adorned with red ribbons, it accompanied the religious service with its bleats.

In some Ligurian villages (Dolceacqua, Pieve di Teco, Pornassio, and others), a strange character dressed in white, armed, and with colourful clothes, called “lambardan,” was tasked with overseeing the correct behaviour of the faithful that night.