Five Ligurian Places from the Books of Italo Calvino

Open the books of Italo Calvino, and Liguria will come alive from the pages. Here are five Ligurian places emerging from the works of Calvino.

Italo Calvino has brought Liguria to the world. From “Ombrosa,” the city of the Baron in the Trees, so similar to Sanremo, to the mountains of the Ligurian hinterland in “The Path to the Nest of Spiders,” and even in the “Invisible Cities,” visionary and diaphanous, traces of the Ligurian landscape can be found. These five places have sprung from his books.

The “Pigna” di Sanremo

In the “Pigna,” the beautiful historic centre of Sanremo, Italo Calvino set his first novel, “The Path to the Nest of Spiders.” The details and descriptions of the streets and houses, in quick but defined strokes, among roofs that hide and reveal cuts of azure, clothes in the sun, and basil pots, reveal a daily familiarity: young Italo often walked through it to go to school in the centre. From the Pigna, you can also reach the church of Madonna della Costa, the Regina Elena Gardens, and Villa Terralba, where his grandparents lived.

The Road to San Giovanni and Madonna della Costa

“A general explanation of the world and history must first take into account how our house was situated,” thus begins The Road to San Giovanni, one of Calvino’s most “Ligurian” books, made up of stories and memories of Sanremo, like the one dedicated to the road that the young Italo walked with his father and brother to go to the San Giovanni estate. The path started just after Villa Meridiana, Calvino’s parents’ house, near Madonna della Costa, and reached the church of San Giovanni. Today, this path no longer exists, so transformed and disfigured by buildings and condominiums, which, however, Calvino’s pen managed to transform into literary places in “Building Speculation.”

The Merdanzo River

The Merdanzo is a stream approximately 10km long that flows from the slopes of the Ligurian Alps, plunging south of the village of Bajardo and reaching the Nervia at Isolabona. Its name could derive from the miasma of some sulfur springs in the vicinity or from the residues of hemp maceration that was once cultivated and processed in the area. However, this name certainly influenced Calvino: Cosimo, the protagonist of “The Baron in the Trees,” used to go there regularly to attend to his needs perched on an overhanging alder by the watercourse.

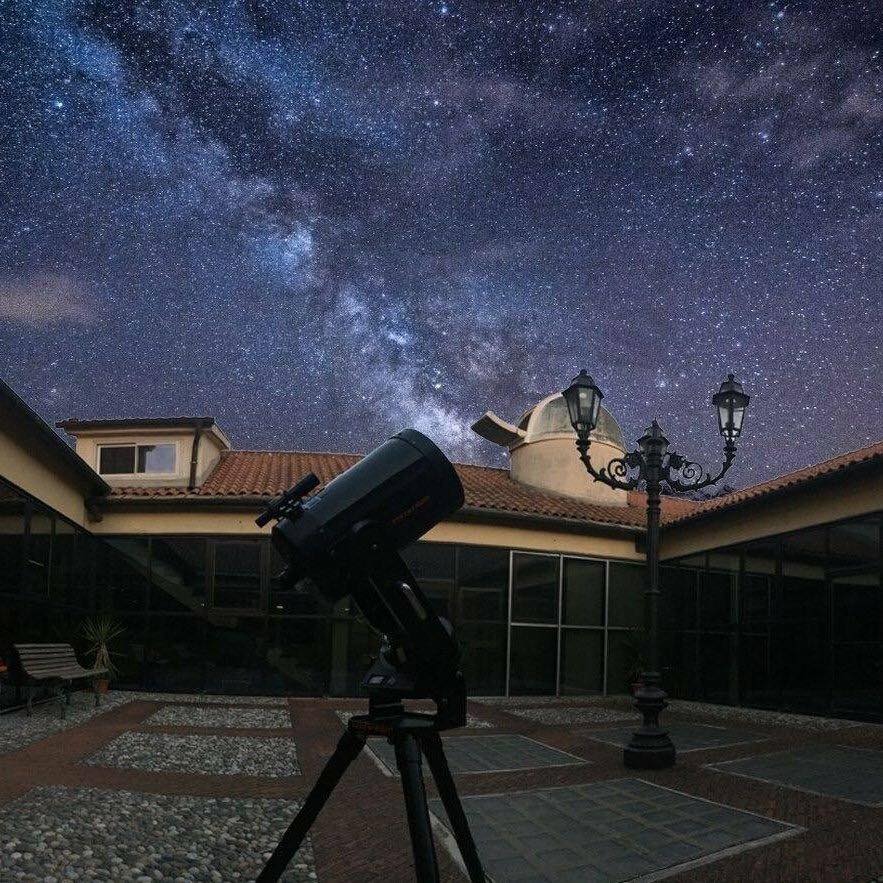

Cassini Astronomical Observatory in Perinaldo

Among Calvino’s later works is “Palomar,” a novel featuring Mr. Palomar, who, taciturn and solitary, has as his main activity the observation of things: sea waves, starling flights, the moon, a cheesemonger’s shop, and much more. His name is derived precisely from his great passion for observation, reminiscent of the Mount Palomar Observatory in California, in San Diego County, one of the most famous in the world, where many types of galaxies have been catalogued. In Liguria, near Sanremo, is the Cassini Astronomical Observatory in Perinaldo, named after Gian Domenico Cassini, astronomer to the Sun King, where, by tradition, the sky has been observed for years due to favourable climatic and atmospheric conditions.

The Mezzaluna Path

It is an ancient, mysterious place that the Ligurians have always known. Situated at 1,452 metres above sea level, it has always been a transit point for transhumance and trade, a crossroad on the Marenca route, a stage for the exchange of cultures and ancestral rites. To reach it, one travels through the beautiful Rezzo forest, near an ancient and famous menhir and a large tabular stone, the Sotta di San Lorenzo, perhaps the destination of ancient sacrifices. This place, likely frequented by the partisan Calvino, appears in the eleventh chapter of “The Path to the Nest of Spiders,” the scene of a harsh confrontation with the enemy.

Ubagu e aprou (Opaco e aprico)

Italo Calvino’s words sometimes achieve extraordinary and absolute effectiveness in describing the world; he is a precise, clear, and exact writer. He was particularly so when speaking of the Ligurian landscape. For example, he invented places that Liguria is rich in but that even Ligurians were unaware of before “From the Opaque,” a text from 1971 later included in “The Road to San Giovanni.” These are the opaque and the sunny (ubagu and aprou in Ligurian dialect), i.e., shaded areas (opaque) and sunny areas (sunny). The former are humid, dark, vertical, desolate; the latter are sunny, clear, expansive, crowded. Certainly, they do not exist only in Liguria, but Liguria, with its contrasts between sea and mountains, hidden villages among the hills and sunny beaches, is rich in them, and perhaps we owe their discovery as landscapes of the soul to Italo Calvino. The experience of the landscape and writing arises from their dialectic.